- Home

- Jane Louise Curry

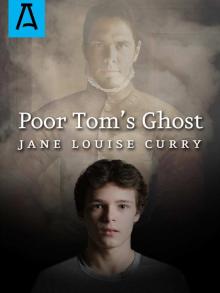

Poor Tom's Ghost

Poor Tom's Ghost Read online

POOR TOM’S GHOST

Table of Contents

Fie on’t, ah fie, tis an unweeded garden

Whose there?

tis but our fantasie

Is not this something more then phantasie?

It would haue much a maz’d you

There is a play to night

O there be players that I have seene play

Ile goe no further

These are but wilde and whurling words

I could a tale vnfolde

I haue shot my arrowe ore the house

And hurt my brother

That if againe this apparision come

Goe on, Ile followe thee

Like John-a-dreames

to say we end the hart ake

what may this meane…?

I will finde

Where truth is hid

Had I but time…

O I could tell you

“…splendidly creepy … a superbly atmospheric story, full of suspense and chilling moments. —Times Literary Supplement

“Absolutely enthralling.” —Publishers Weekly

“…all ends well with perfect emotional logic. Who cares about the other sort when deep in a fast-moving and absorbing story like this one?” —Jill Paton Walsh

“…a solid, breathlessly sustained ghost story.” —Kirkus Reviews

“If you buy this for your pre-teenager and don’t read it yourself, you are missing a memorable reading experience, and a very poignant evocation of the pre-adolescent mind.” —Marion Zimmer Bradley

“…tremendous power, compelling the reader to total surrender … a book which approaches greatness.” —The Junior Bookshelf, U.K.

POOR TOM’S GHOST

Jane Louise Curry

Poor Tom’s Ghost

All Rights Reserved © 1977, 2013 by Jane Louise Curry

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the author.

First Edition published 1977 by Atheneum Publishers. This digital edition published by KMWillis Books c/o Authors Guild Digital Services.

For more information, address:

Authors Guild Digital Services

31 East 32nd Street

7th Floor

New York, NY 10016

ISBN: 9781625360168

POOR TOM’S GHOST

Poor Tom

He puts on Hell like a suit of clothes

To wear it walking in the Town,

For who would think that Hell could pose

As a London suit and French silk hose

Out buying its lady in a satin gown

Or giving a beggar half a crown?

Poor Tom

It strolls on aimless, well-shod feet

To buy its wine and cheese and bread.

It smiles at maidens roundly sweet

And helps blind crones across the street.

It moves its eyes and turns its head,

For it’s alive and poor Tom’s dead

Poor Tom

—OLD SONG

Fie on’t, ah fie, tis an unweeded garden

“WHAT ARE WE LOOKING FOR?” Roger asked his father.

“A turning on the right.” Tony slowed the old Ford estate car down to twenty and cast an uneasy eye at the boat trailer looming in the wing mirror. From time to time along Park Road a grey mini had drifted out so that its driver could peer around the dinghy on the trailer. He could not tell whether it meant to pass them or not. “It’s along here somewhere—before the first house, according to Aunt Deb’s Mr. Carey.”

Jo, beside him, pointed. “Could that be it? Or is it just a break in the fence? It looks a bit jungly for a driveway.”

Tony’s eyebrows shot above his sunglasses as he switched on the boat trailer’s right-turn indicator and braked carefully to a crawl. “Unh! Knee-deep in grass. But if that’s not it, I don’t know what is. Roger?” He turned toward the back seat, the high spirits he had been in all the way from central London out to Isleworth a shade dimmed. “Be a good fellow and have a look out your window; if that nervous mini’s still behind us, wave him round, and then nip across to see if that’s the lane we want. I’m no good at backing this rig, so once we’re in, we’re in.”

“O.K., Pa.” Roger thrust his head out the rear window on the traffic side, saw the mini lurking and, after a quick look for oncoming traffic, beckoned violently. The little grey car and its plump, grey-haired driver swung out and past with a wave, slowing as it came abreast of the high brick wall ahead and turning left into Syon Park. Tony brought the Ford to a full stop, and ten-year-old Pippa caught hold of Sammy, the longtailed bushbaby, as Roger opened the car door.

Roger, gaining the opposite side of the tree-lined road and the grassy, gravelled track Jo had spotted, fought the urge to hunch over to ease the nervous spasm that tightened his stomach. Until just now it had not occurred to him that the house might be dreadful. A gingerbreaded monstrosity. A mildewed horror mouldering away under a mat of ivy. It might be anything. “A great house. Wait and see. You’ll be mad about it,” his father had said with an air of mystery. But if his dad hadn’t seen it since he was a kid… And actually, he had probably forgotten all about it until last week. Certainly he had never mentioned it during Roger’s thirteen years. According to Great-aunt Deb’s lawyer, it had been standing empty for three months. That explained the overgrown drive, but what if it also meant mildew and damp rot, rising damp and woodworm, vandalism even, or vermin? It couldn’t. Everything had been going so well all day. In fact, everything had been going so well since Friday a week ago when Tony gave his first performance in Hamlet at the National Theatre and earned himself a sheaf of favourable newspaper reviews. It couldn’t fall apart now. They had sung the whole of the way down—“I’m Henery the Eighth, I Am!” and “If it Wasn’t for the ’Ouses in Between.” Even a tearjerking rendition of “If Those Lips Could Only Speak” in harmony.

The cramp in Roger’s stomach bit sharply, but eased as he bent over to examine something in the grass beside a fencepost. Please God, he prayed fiercely, don’t let Pa just take one look at it and dig in his heels. Straightening, Roger yelled across the road. “Pa? This has to be it. There’s a stone marker here with COX carved on it.”

Tony acknowledged the news with a half-salute and after a television repair van coming from the direction of the river had passed, he pulled across the road in a neat arc, easing the single-axle trailer into the narrow lane with inches to spare.

“I do believe the old man’s improving,” quipped Roger as he climbed back in beside Pippa.

Jo gave a little snort of laughter, but Pippa looked at Roger solemnly, as if she sensed the tension under the flippant tone.

Tony pulled a long face. “Don’t remind me. I’ll have to repaint the gate at home after this afternoon’s performance.”

The lane, a right-of-way that did not actually belong to the old Cox property, ran narrowly between a brick wall on the left and the stout rail fence of the field to the right. Tony drove cautiously, with an eye on the right-hand wing mirror. Roger leaned back with one arm on the wicker cat carrier, trying to look unconcerned, but Pippa hung over the back of the front seat, watching eagerly for the first glimpse of a house.

Tony looked every bit as eager as Pippa, but Roger detected—or imagined he did—a hint of defensive irony in his father’s tone as he remarked, “Aunt Deb used to call it Castle Cox.”

“Then we’ll have to call it Castle Nicholas,” Pippa said.

“Right you are, Pips.”

Jo smiled lazily. “Tony, you’re a

fraud. You groan at the thought of being tied to a house, but you’re as excited as a kid. You’ve never actually been in it, have you?”

Tony, driving with one hand, drummed his fingers rhythmically on the edge of the car roof. “Not much further in than the front door, but I thought it was a great place, what I saw of it. The old lady who lived here—she was my great-grandmother—” he explained to Pippa, “was ninety-three, and I was six or seven. Aunt Deb brought me down because she thought the old lady, hermit or no, might like to meet the last of the line before she shuffled off this mortal coil. An ancient female left us for what seemed hours in a long, high entrance hall full of dusty aspidistras, and in the end the old lady refused to see us at all. She’d quarreled with all of her relatives fifty years or more before and wasn’t about to make it up. Uh-oh!” Tony braked quickly, then opened his door to lean out and look behind. Closing it resignedly, he said, “Snagged again. Take a look, will you, Rog? What’ll happen if I just keep on going?”

Roger clambered out to inspect the fencepost that had caught the trailer’s right-hand mudguard. “You’d make it two in one day.”

“Hell,” Tony muttered. But he backed up several feet and then eased the trailer wheel safely past. “I was trying to keep well clear of the wall for the sake of our nice, fresh varnish,” he grumbled, exaggerating blandly. The boat was not so wide as all that. “We shall just have to creep.”

“Finish your story,” Jo prompted. “If Great-grandmother Cox was ninety-three then, how old was she when she died?”

“Ninety-nine, the poor old witch, only a hair short of a hundred. She missed her letter of congratulation from the Queen by three days. Then the house came to Aunt Deb as next-of-kin, and she wrote to me at school about it. It was crammed to the rafters with rubbish—newspapers, magazines, empty jars and tins—and every Christmas gift Aunt Deb had sent her for thirty years, every one of them still in its Christmas wrappings.”

“But that’s crazy,” Pippa protested, wide-eyed. How could anyone not open a Christmas present?

“Crazy or nasty,” Jo agreed, equally impressed.

Roger, who had never heard the tale of old Mrs. Cox before, forgot his careful pose of detached interest. “But Pa? If the house was left to Great-aunt Deb all that long ago, how come you never came back?”

“Oh, the place was too big for Aunt Deb, and too far from town, so she had it cleaned up and then let it. According to Mr. Carey, there was a steady stream of tenants up until the early sixties when a local builder took it over as a warehouse of sorts. He cleared out in ’75, and since then the, Children of Nod, one of Aunt Deb’s obscure charities, have had it as a hostel.”

“The Children of Nod? That’s a funny name,” Pippa said.

“It’s from the Bible, isn’t it?” asked Jo. “ ‘The land of Nod on the east of Eden’ where Cain went after God cursed him for killing his brother Abel?”

Tony nodded. “Though I believe that the hostel took in rather less spectacular outcasts.” He smiled. “Dear Aunt Deb. I wish she’d lived long enough to have been in the best seat in the stalls last Friday night to see my Hamlet. She was passionately fond of Shakespeare even if she did tend to muddle one play up with another. She always said I’d have my chance at Hamlet.” He paused, frowning at the way ahead. “What have we here?” Coming from the shade of the lane into a patch of bright August sunshine, the car’s pace slowed from a creep to a full stop. The brick wall bent sharply to the left; the fence angled away to the right, and the grass-grown drive went both ways, disappearing into a jungly green shade.

“ ‘Fie on’t, ah fie, ’tis an unweeded garden’,” Tony quoted—a shade apprehensively, Roger thought. And it was pretty bad. A machete and chain-saw would be more to the point in such a garden than Jo’s nippers and clippers.

“Away with your pishery-pashery. It’s a challenge!” Jo did an eeny-meeny between the two lanes and said decidedly, “Me for the right-hand way.”

“Me too,” Pippa seconded.

“Roger?”

“Me? Oh, whichever.”

“Six of one and half a dozen of the other so far as I can see,” Tony observed, taking the way on his right hand. “I don’t actually remember, but I would guess that the driveway circles past the front of the house and back out again. For making sweeping entrances. I—” He broke off, stalling the car as he braked abruptly without engaging the clutch.

“Lawks-a-mussy!” Jo said inelegantly. She stared at the house that had materialized amidst the trees. “Tony, no! Tell me we’ve come wrong. We have come wrong, haven’t we?”

For the house was awful. It was an ugly, streaked, once-pink pile, not so much large as lumpish: a tall, awkward box pretending to be a castle. The roof was bordered with a crumbling crenellated parapet and absurd little turrets stuck like birthday candles along its length. The ground-floor windows were boarded up with plywood, the entrance porch and padlocked front door with corrugated metal sheeting.

“Goddlemighty, what a horror!” Tony shook his head unbelievingly. “I don’t remember its being like this. Oh, blast! Can’t you just hear what old Alan will have to say when he comes down on Sunday? Well, I won’t have it. I won’t be caught dead in that thing. It’s so silly it’s obscene—worse than that incredible Californian ‘Royal Camelot Fish and Chip Palace’ in Santa Monica.”

“Castle Nicholas,” Jo gasped. She tried hard not to laugh.

“Oh, shut up.” Tony glowered.

Pippa, already struck silent, stroked Sammy and frowned at the house as if it were upside-down or out-of-focus, and squinting might help.

“Well,” Tony said at last, “the first thing I do when we get home tonight is telephone Alan and put him off for Sunday. If that idiot caught sight of this we’d be done for. ‘Where’s your sense of bloody humour?’ ” he mimicked. “And ‘It could be the poor man’s Strawberry Hill. Think of the hysterical parties you could throw.’ No thanks.”

“But we can’t go home tonight!” Roger was stricken. “We brought the camp beds and sleeping bags. And the boat. What about the boat? You said we could take it out on the river tomorrow or Sunday. We’ve not had it out in two years.” He opened his door and jumped out, his mind racing like a squirrel in a cage. The house was beyond apology, but… “Even if we don’t stay, we should leave the boat here if there’s a garage. ‘No more than a thousand feet from the river’—isn’t that what that solicitor, Mr. Carey said?”

“Um.” Tony moodily rested his chin on his wrists crossed on the steering wheel. “I suppose we ought to. August isn’t the month to look for a mooring on the Thames. And I did promise. Jo?”

“Who, me? Please yourself. I can stand anything for a weekend, so long as there aren’t bats. One bat and I’m on my way back to Hamilton Terrace.”

“Helpful, aren’t you? Well then, we’ll see…”

Roger was off and away. “I’ll see if there is a garage,” he called over his shoulder. Behind him, Jo was already out of the car, stretching her elegant, skinny length, and a martyred Tony was re starting the motor so that he could pull up in front of the house. Oh pleasissimus, God, thought Roger, let us stay the weekend and Alan come Sunday and make Pa see the house could be a wonderful joke. And make Alan bring Jemmy so he can’t flirt with Jo and sink Pa in the sulks. We may never again have a chance at a house.

Not that the Nicholases were precisely hard up. Tony was a successful actor and besides his fairly steady stage work in London, had over the past ten years made good money in films. But there was precious little to show for it. Tony was sentimental, generous, occasionally bloody-minded, occasionally melancholy, usually cheerful, and incapable of saving tenpence. If he decided to sell the house Great-aunt Deb had left him before they found another that really suited, that would be the end of it. A few friends with hard-luck stories, a few splashy parties, perhaps a new and bigger sailboat—on top of a whacking tax bill from the Inland Revenue—and farewell house money. If the Nicholases had ever felt a pinch, To

ny and Jo might have grown a shade uneasy with their butterfly existence. But somehow there was always good food, a comfortable flat, even a garden for Pippa’s pets and Jo’s collection of potted herbs and flowers. That it was always somebody else’s flat and garden never seemed to bother them. Their present perch in Hamilton Terrace in St. John’s Wood was the sixth since their return the previous summer from a year in California. Jo had gone directly into rehearsals for a play at the Lyric, and Tony had the good luck to be invited to rejoin the National Theatre Company shortly after its move to the new complex on the Thames’ Bankside. Neither had time to spare for house-hunting. And, after all, why rent when the Overburys were off to New York for a two-month stint in a play there and had offered the use of their house off Chelsea Green? Muswell Hill, Farm Place, Oak Village, Campden Hill and Hamilton Terrace had followed, each offer turning up as if on cue. The world was full of friends.

After all they were charming, the Nicholases, footloose and amusing. Everyone said so. “Of course Pippa is a bit of a puzzle, but wonderfully decorative, my dear, with that cloud of red-gold hair and that sweet wide-eyed animal—what is it? a bushbaby?—always on her shoulder. And Roger? Quite the charmer. Another five years and Tony will have to look to his laurels. Wonderful family. Weathered some rough seas, too.”

Wonderful, maybe. So everyone said. But seaworthy? More like a four-log raft lashed together with string and sticking plaster. Having a house of their own might not change anything, but… Roger, rounding the east corner of Castle Cox, drew a deep breath and shut his eyes thankfully. There was a garage: an ugly concrete block box of a thing with corrugated iron doors, but a garage.

“Found it, Pa!” Roger called.

Tony appeared with his hands in his jeans pockets and a faintly mulish curve to his mouth. “The question is, is it long enough?”

Poor Tom's Ghost

Poor Tom's Ghost